Saving Young People From Themselves – Steve Rattner

StevenRattner.com: Saving Young People From Themselves

|

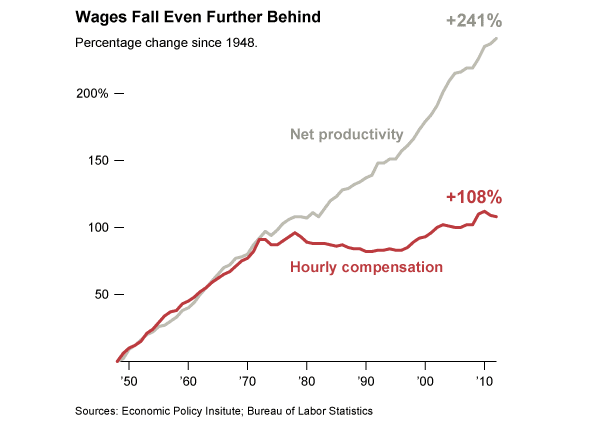

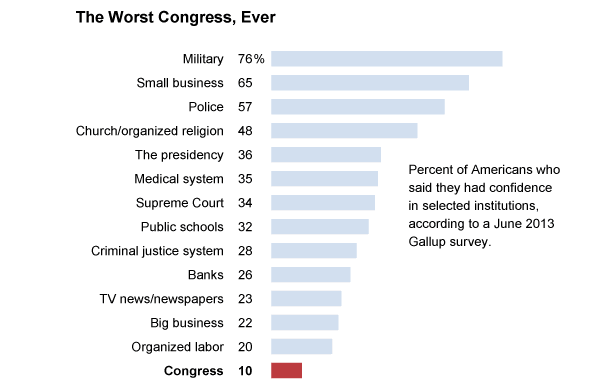

Saving Young People From Themselves Posted: 13 Apr 2014 11:38 AM PDT Originally published in the New York Times. RETIREMENT is a financial obligation that today’s younger generations are not handling well. That may be through no fault of their own — they suffer from lower incomes, after being adjusted for inflation, and student debt that makes it a struggle to save. But regardless of the reason, the failure to save for retirement is setting up Americans in their 20s and early 30s for financially stressed golden years. The statistics are startling: Only 43 percent of eligible workers under 25, and 62 percent of those between 25 and 34 participate in 401(k) plans, compared with 70 percent or more of those over 45. And the young contribute less — 4.3 percent of income for those under 25 and 5.5 percent for ages 25 to 34. In contrast, Americans between 55 and 64 direct 8.7 percent of their incomes to these plans. Skimpy retirement assets might be manageable if they were being offset by other wealth accumulation. But that hasn’t happened. In fact, adjusted for inflation, members of Gen Y — those born after 1980 — are poorer than their parents were at similar ages. We should address this looming crisis via a radical restructuring of our retirement plans, including mandated savings. While the saving problem may be acute for young people, it’s hardly limited to them. After rising during the financial crisis, the overall savings rate of Americans has once again declined to paltry levels. For those who have saved and invested in equities, the surge in stock market prices since the recession ended has helped, which has pushed up the value of retirement holdings. But in an unfortunate irony, many millennials, who watched share prices collapse in 2008, then steered clear of the market, thereby missing out on its rise. Typically, these young Americans keep about half of their portfolios in cash — not a sensible long-term investment strategy. Earlier this year, to take a stab at addressing the retirement issue, President Obama proposed a new form of Individual Retirement Account that would allow Americans with household incomes below $191,000 to put aside money that would accumulate tax free. Unfortunately, the Obama idea is only a symbolic and inadequate gesture. For one thing, its cap of $5,500 per year is too small, and it lacks automatic enrollment or mandatory employer-contribution. For another, contributions would initially be invested at low Treasury rates. Younger workers should be investing mostly in equities, which, over time, should provide higher returns. Under the Obama plan, when an individual’s account reached $15,000, funds would be moved into an investment offering from the private sector, which would confront people with the same daunting and unfamiliar choices that face holders of 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts. A better idea, but still offering only marginal improvement, is the one proposed annually by the president and ignored annually by Congress: requiring employers who do not provide 401(k) programs to offer automatic enrollment in I.R.A.s. I’d love to see the restoration of defined benefit pensions, which combined automatic saving and sensible, long-term investment strategies. But that’s not going to happen. So at the least, we should take the responsibility for managing retirement funds away from ill-equipped individuals. To that end, Senator Tom Harkin, Democrat of Iowa, has proposed a plan that would offer a more certain retirement benefit than existing individual plans provide, together with automatic enrollment, universal coverage, portability from employer to employer and professional management. However, Senator Harkin’s plan has its own flaws — it doesn’t require any employer participation, and participants would be allowed to reduce their contributions or opt out entirely. The best solution would take up the question of mandated savings. I understand that in today’s world of stagnant incomes, forced savings mean less money for individuals to spend now. But would we seriously prefer that our children become impoverished senior citizens? The approach I like is Australia’s superannuation program, which requires that 9 percent of workers’ pay be diverted into retirement accounts. Tax incentives are also provided, to encourage additional deposits. The superannuation funds collectively have $1.7 trillion in investment assets. Adjusted for population, that’s the equivalent of $25 trillion for the United States, over twice what Americans have parked in 401(k)s and I.R.A.s. That’s an idea worth considering. Young Americans are on track to be worse off in retirement than their parents. Let’s not just sit by and watch that happen. |